Category Archives: Museum For All

Museums during lockdown

After more than one year struggling under the different waves and varieties of Covid, everyone is certain about how this situation has affected and will affect our lives in many ways. Museums are not exempted of the reach of this disease and the difficulties that it carries with.

According to UNESCO, since the beginning of the Pandemic, almost all museums around the world have been temporarily closed. The reliance on tourism has affected them mostly financially, which also has an impact on the exhibitions that can be planned. Seen this, museums have been quick to react to the situation by offering different ways to enjoy their collections – some of which are much more accessible than those offered before the pandemic. ICOM went deep into this and pointed out in a 2020 report that museums have increased their online activity around a solid 15%.

This post will give an overview of these activities, following the very interesting and useful research of Chiara Zuanni, assistant professor in digital humanities at the Centre for Information Modelling at the University of Graz. The result of her research can be consulted in both an Europeana portal and in a map that gathers all the different online activities that museums have followed during the last months in order to face this health emergency panorama. It is still possible to collaborate with the configuration of this map by sharing information about online activities carried out by museums.

Regarding the different activities and tasks that museums engaged during the harshest moments of lockdown, we find two main initiatives:

On the one hand, there is maintenance of the museum’s facilities and collections. The focus here was set on the conservation, restoration and digitalization of the pieces and documents found both in display and in the archives. This digitalization makes the museums’ heritage more accessible and also supports other outreach and research work. This BBC article, written by Francesca Gillet, sheds light on these “secret life of museums during lockdown”, focusing on museums and galleries in London.

On the other hand, we find a more active online engagement, promoting “a broad range of digital projects and activities” to support “access to cultural heritage and maintain a relationship with their audiences” (Zuanni, 2020). The interesting fact of these activities is that not only the average museums’ audience participated, but also they were followed by a new and curious audiences staying at home. How was this possible? We have to thank social media.

Through different hashtags, challenges and streaming cultural content online, to TikToks and video games (Nintendo’s franchise Animal Crossing added works of art from many art institutions like the Getty Museum and the Metropolitan Museum of Art), museums have become part of our everyday life, filling our homes with art and culture.

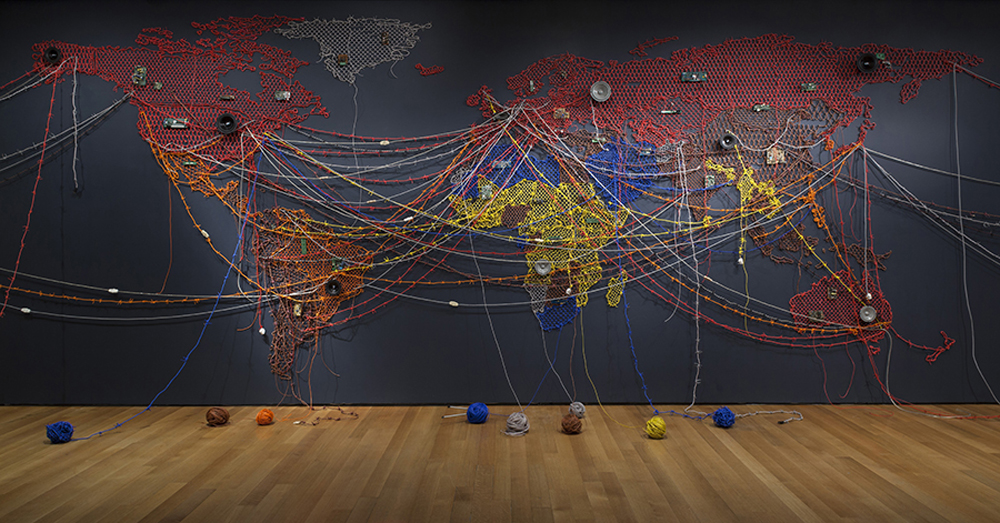

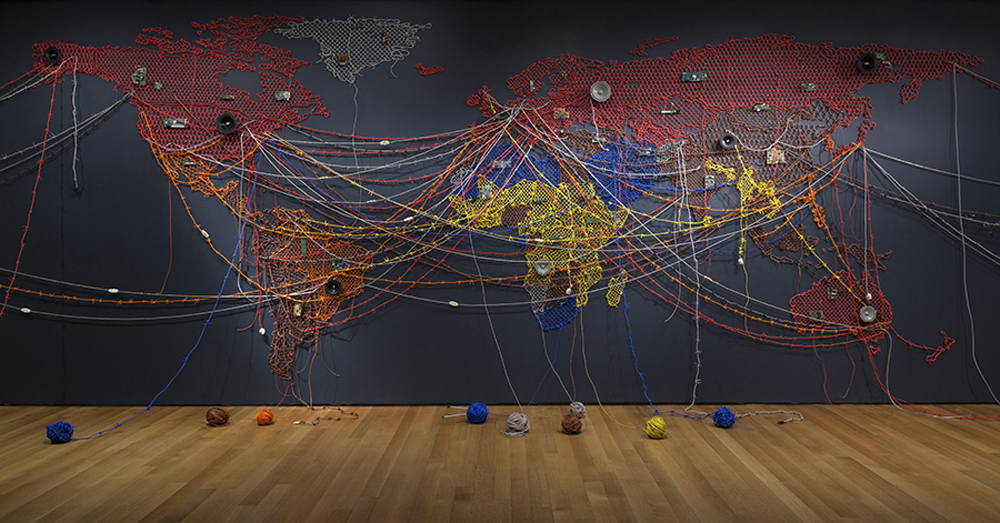

Discussing the map resulting from Chiara Zuanni’s research displays several elements: Contemporary Collecting (appealing to memories and experiences of the pandemic), Social Media Projects, Virtual Tours, Online Exhibitions, Games, Educational Content, Tweets, and Other Activities.

Here we’ll provide some interesting examples.

Starting with Social Media Projects, the most fun of them have been those encouraging audiences to reinterpret pieces displayed on museums with whatever they found on hand. The hashtags #gettymuseumchallenge and #tussenkunstenquarantine inspired other institutions to present their challenges and so welcome and share their audience’s creativity. Other hashtags like #ClosedButActive were mostly used on Twitter in order to give peeks of their collection and activities to the online community. An interesting reading on this initiative was #MuseumAlphabet, which encouraged all kinds of museums and institutions to name a piece, author, or curiosity about their collections after each letter of the alphabet. All of these hashtags were used on Instagram, Facebook and Twitter.

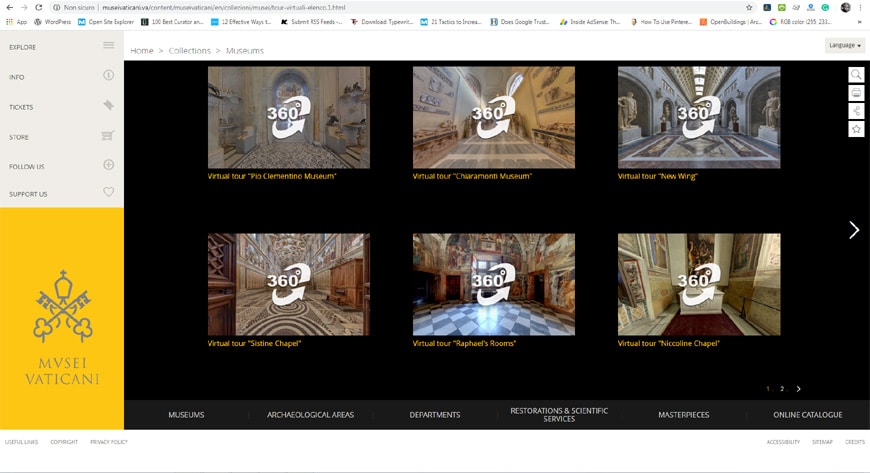

However, when it comes to streaming content, the bigger museums shined with their virtual visits. Museums such as the Musei Vaticani (Rome), the Louvre (Paris), the MoMA (New York), the Victoria and Albert Museum (London), and the Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza (Madrid) are just a few examples of institutions that have undertaken a huge task of digitalization and video editing so that anyone can visit them from their living room. To find out more, the New York Times reported several examples of museums and historical places offering online tours all around the globe. You can read the article here.

Not only pre-existent museums were offering digital tours and activities. Regarding Contemporary Collecting, some museums have launched campaigns to create and curate exhibitions based on the memories and testimonies of people during the pandemic, and even new museums have appeared. Frankfurt Historisches Museum and Wien Museum (Viena) offer good examples of exhibitions that are to be curated and completed through the audience’s participation, and initiatives like Minnen (together with the Nordic Museum in Sweden) or The Covid Art Museum reflect the creativity and reception of the lockdown within the social imaginary, compiling elements ranging from texts and photographs to memes.

In conclusion, and according to what Martin Bailey wrote in The Art Newspaper: “Covid have changed in long terms conditions how we are visiting museums and how we will visit them in the future”. This not only affects the physicality of the museum experience, but has also underlined other elementary needs within the planning of exhibitions and museum activities, as well as raised new questions. After seeing the positive impact of online activities in museums’ websites, it is clear that a good digitalization process is fundamental for museums not to fall in ostracisms. But it is also questionable how, despite of the fact that these online activities have make more people aware of what museums are doing and how important they are to enrich the social fabric, there is also a part of population that cannot access internet and therefore are excluded of any cultural itinerary or initiative. Online engagement have make a huge impact on the museums’ race for accessibility, but we should keep our eyes open to everything what is happening in our society if we really want to be museums for all.

Inclusion in Museums, to celebrate International Museum Day.

Tactile Studio asked people what Inclusion brings to the Museum. Take a look at the video in this post:

https://www.linkedin.com/posts/tactilestudio_what-does-accessibility-and-inclusion-bring-activity-6800408146427830273-bKe1

Museum for All and ARCHES: towards inclusion in museums.

Museum for All is a platform that has been running since 2012 and whose main focus has always been to promote accessibility to museums and cultural centres regarding the needs and variety of their audiences. In this sense, its path relates to the H2020 European project ARCHES, which stands for “Accessible Resources for Cultural Heritage and Ecosystems”.

This project has been developed within three years by different partners, such as research institutions like the University of Bath and The Open University, technological companies like Singtime and Coprix Media, and –most importantly- museums all around Europe such as Museo Thyssen-Bornemisza (Spain), the Victoria and Albert Museum (United Kingdom), the Kunsthistorisches Museum Wien (Austria), Museo Lázaro Galdiano (Spain), the Wallace Collection (United Kingdom), and Museo de Bellas Artes de Asturias (Spain).

ARCHES has brought together disabled people, technology companies, universities and museums in order to develop technical solutions such as tactile reliefs made with the latest 3D modelling techniques, barrier-free apps and games for smartphones and tablets, sign-language avatars and other cutting-edge techniques oriented to a better sensorial and cognitive experience of the museum. These technologies have been co-designed and tested by more than 200 disabled people in Spain, Austria and the United Kingdom.

This video shows an introduction to the project made by some of the people who participated in it.

As the video points out, ARCHES did not aim to differentiate between one type of disability and another, but to provide a better experience of the pieces displayed at museums for everyone visiting them. In order to achieve this, the research team –made up of members of universities, museum professionals and people with different disabilities- have put together a series of workshops to promote active participation, taking into account and paying special attention to the guidelines and needs expressed by disabled people.

It is at this point where ARCHES and Museum for All meet together. ARCHES’ main objectives and research methodologies match the protocols that Museum for All intends to follow, always taking into account the opinion and participation of the museum’s users in order to improve spaces and experiences. ARCHES’ website contains a list of the objectives and work packages followed during the development of the project, which can be briefly summarized in the following ideas:

- ARCHES focusses on develop and evaluate strategies to put new technologies at the service of people with differences and difficulties associated with perception, memory, cognition and communication in order to enable their inclusion in museums.

- The project also works on identifying sources –Internet, internal archives, libraries, etc. – that could integrate this content into innovative tools and on inserting them in operational environments based on participatory research.

- The main purpose of this is to work with cultural heritage sites and museums to help them engage with a wider range of audiences promoting the tools and applications developed by this participatory research by means of on-site demonstration activities.

Taking these as a base, Museum for All wants to explore how all of it can be applied to smaller museums –which is one of Museum for All’s main objectives- and also include other groups and other needs that involve family models (looking specially at tour and spaces for children), lifestyle (promoting options in museum’s cafés for vegan and vegetarian people, allergies, diet restrictions, etc.), and ethical commitments (such as social inclusion beyond disabilities, gender representation, ageing, etc.). The tracking on how apps and other technological, structural or planning facilities can help to make museums more bearable and accessible taking into consideration the variety and plurality of public is another thing that Museum for All and ARCHES have in common, thus ARCHES methodology serves as a basis for carrying out and realizing these objectives.

ARCHES’ results are to find online and put at the service of museums and the cultural community. They are available in three languages (English, German and Spanish) and focus on the implementation of participatory methodologies towards a wider inclusion in museums.

If you are interested in reading more about these far-reaching commitment that Museum for All has towards inclusion, please check out our posts “Beyond Disabilities” (I, II, and III). At Museum for All we know that these aspects can still be expanded and that there is still a long way to go for museums to become a place of encounter and representation, of memory and expression, also contributing to contemporary realities of contemporary people who use and experience them – something that has changed and will continue to change over time, preferably towards a more inclusive and plural society.

Art, Museums and Digital Cultures — CONFERENCE

In the upcoming days, 22nd and 23rd April, will take place online the International Conference ‘Art, Museums and Digital Culture’. The Conference’s main aim is to provide a space for discussion to different experts, researchers and organizations about how digital technologies have contributed to the creation of new territories and so have stimulated other innovations in artistic production, curatorial practices and museum’s spaces –all this in a time of greater and deeper interest in the impact of technologies on society. This conference is coordinated by the Instituto Superior Técnico of the University of Lisbon, Instituto de História da Arte and Faculdade de Ciências Sociais e Humanas from the NOVA University of Lisbon and the Museum of Art, Architecture and Technology (maat) of Lisbon.

The different sessions draw a wide perspective on digital art practices, going from strategies for digital integration in both artistic, museographic and curatorial itineraries, to collaborative policies and methodologies that bond together art, technology and society. The keynote speakers are focused on new technologies, finding proposals about Machine Learning and Systems of Knowledge related to art creation (Anna Ridler), about how the new technological dynamics have affected all different kinds of publics (Felix Stalder), and how museums can adapt themselves to the post-digital era also regarding accessibility (Ross Parry & Vince Dziekan).

The EU-funded Project “Accessible Resources for Cultural Heritage EcoSystem” (ARCHES), carried out within the framework of an H2020 research project, will present in this conference. Partnering with ArteConTacto and Museum for All, their representatives (Rotraut Krall, Moritz Neumüller and Andreas Reichinger) will elaborate on their pioneer participatory research approach to digital technologies in the museum in order to make them more accessible. Technological tools such as tactile reliefs, apps and games for smartphones, and sign-language avatars have been designed and tested by more than 200 people in three different research groups in Spain, Austria and the UK. These groups were also made up of very different people with different necessities and interests, thus representing different views and experiences and also highlighting the disabling consequences of social attitudes sometimes carried out by museums and other cultural institutions.

Among the different strategies carried out by ARCHES during its research, this conference will focus on two examples of solutions for a better understanding of two paintings in particular: The Laughing Cavalier (Franz Hals) for the Wallace Collection in London, and The Peasant and the Nest Robber (Pieter Bruegel the Elder) for the Kunsthistorisches Museum in Vienna. Both examples count with a 3D print of the painting stressing out different aspects of each piece and also complementing them with other resources like Easy Read texts and Soundscapes. All these strategies were though in order to better address the needs of museum visitors, also pointing out how technology can be good, useful and beneficial to everyone. The educational team of the different museums that participated with ARCHES expressed that their strategies and tools when working with disabilities and in participatory environments have deepened with this participative methodology, so it avoids solutions developed ‘for” these particular users, instead of ‘with’ them.

For more information on this project and also getting a wider perspective on digital technologies and inclusive strategies and innovations in artistic production, please contact museumdigitalcultures@gmail.com. Registrations for the conference are open until April 16th. You can also read more about this specific project (‘Please Touch! An inclusive art experience’) in ARCHES’ website.

Contemporary collecting. An ethical toolkit for museum practitioners

Edited by Ellie Miles, Susanna Cordner, Jen Kavanagh 2020

This is an excellent resource from the London Transport Museum.

Download it as a PDF, or read it hereafter in simple (and screenreader accessible) text.

This toolkit explores some of the ethical judgements that contemporary collectors make and offers case studies, reflection, guides and further information for those interested in the subject.

London Transport Museum, 2020

Contents

3 Introduction to the toolkit

4 Contributors

5 Theme 1. Hate, ‘both sides’ and the idea of balance

Introduction by Ellie Miles

Collecting ‘hate’: questions for consideration by Jen Kavanagh Case study: Sam Jenkins, People’s History Museum

10 Theme 2. Decolonisation of museums

Introduction by Ellie Miles

Top tips for decolonial practice in contemporary collecting by Rachael Minott, The National Archives (UK) Case study: Charlotte Holmes, Birmingham Museums

16 Theme 3. Climate emergency

Introduction by Ellie Miles

Climate emergency questions and prompts by Ellie Miles Case study: Laura Boon, Royal Museums Greenwich

22 Theme 4. Trauma and distress

Introduction by Susanna Cordner

Working with trauma by Matt and Jess Turtle, Museum of Homelessness Case study: Jen Kavanagh, Kingston Centre for Independent Living

31 Theme 5. Digital preservation

Introduction by Susanna Cordner

Getting started in digital preservation by Bill Lowry, Museum of London Top tips for ethical digital collecting by Arran Rees, University of Leeds

Case study: Elisabeth Boogh, Stockholms Läns Museum; Anni Wallenius, The Finnish Museum of Photography; and Bente Jensen, Aalborg City Archives.

45 Reading group information

Introduction to the toolkit

Contemporary collecting involves people making decisions about preserving lived experience, knowledge, stories and objects and as such can venture into complicated ethical territory. This toolkit explores some of the ethical judgements that contemporary collectors make and offers case studies, reflection, guides and further information for those interested in the subject.

The toolkit aims to be a useful resource for people embarking on contemporary collecting or with some previous experience of the practice. It is also for anyone wishing to learn more about some of the processes. It offers insight from practitioners who have been leading this work and have reflected critically on their practice. This document can be

read alongside the Contemporary Collecting Toolkit by Jen Kavanagh published in 2019 by Museums Development North West.

The judgements and considerations that museums make and take with regards to contemporary collecting have not yet been formally codified or assessed.

This toolkit therefore provides a record and some accountability for the work happening now and aims to document some of the judgements and considerations that museum workers undertake in their collecting.

During 2019, in consultation with the Contemporary Collecting Group and through workshops and survey research, we identified a series of topics that intersect with contemporary collecting in different ways. Topics of interest that emerged where contemporary collectors make ethical judgements were: balance, decolonisation, climate, trauma, digital preservation and data protection. We recognise that this is a partial list, and hope that we can update, expand and re- issue this document over time to include more perspectives, more insights and more learning

as fields develop. Please feel free to share your comments with us at: documentarycurator@ltmuseum.co.uk.

The toolkit should be considered in the context of: material produced by the Museum’s

Association including the Code of Ethics and reports such as Museums Change Lives and Empowering Collections; the work of the

Collections Trust; the body of work around

ecological and nonhuman ethics; the toolkit on contemporary collecting by Jen Kavanagh and Museum Development North West; significant legislation like the Equality Act 2010; and a

variety of policies and procedures specific to

individual institutions. We have also included some references to texts across the different

themes, which we hope provide a useful starting point for those keen to learn more.

Ellie Miles, Documentary Curator,

London Transport Museum March 2020

Contributors

Contemporary collecting: an ethical toolkit for museum practitioners was produced as part of the Documentary Curator programme at London Transport Museum (LTM) and funded by Arts Council England.

It was written and edited by Ellie Miles and Susannah Cordner (Documentary Curators, London Transport Museum) and Jen Kavanagh (freelance curator and consultant), who also authored a case study. Ellie Miles also facilitates the Contemporary Collecting Group. Since her work on the toolkit, Susanna Cordner has left London Transport Museum, and now works at the London College of Fashion. The other content and case studies were written by Rachael Minott (The National Archives, UK), Sam Jenkins (People’s History Museum), Charlotte Holmes (Birmingham Museums), Laura Boon (Royal Museums Greenwich), Matt and Jess Turtle (Museum of Homelessness), Bill Lowry (Museum of London), Arran Rees (University of Leeds), Elisabeth Boogh (Stockholms Läns Museum), Anni Wallenius (The Finnish Museum of Photography) and Bente Jensen (Aalborg City Archives).

Hate, ‘both sides’

and the idea of balance

Introduction

Ellie Miles, London Transport Museum

Political opinion is acutely divided, and many people will encounter media and consume culture quite separately to those with opposing views. Museums and museum collections are one place where visitors are witness to the same thing.

Organisations, including museums, have claimed neutrality by presenting ‘both sides’ of a debate. This model typically involves presenting an issue as contentious and then giving space to, and representations of, two or more points of view before retreating from further comment. One of the best documented examples of this strategy in the museum sector concerns the debate in the 1990s around the display of the Enola Gay aircraft that bombed Hiroshima (see Zolberg, 1995). Such representation strategies practices are also now commonplace in broadcast and other media.

These decisions can be misjudged. When this process fails it causes harm by exposing people to hate material and by giving credibility to hate groups.

Sometimes issues are presented as contentious, but must be accepted nevertheless – broadcast media has done this extensively with climate change. Sometimes a debate is presented so that one ‘side’ is compelled to defend their existence. Poor framing can cause harm if the perspectives of certain groups are shown as emotional rather than

informed. Museum workers acquiring contemporary material and supporting other museum work should research, consult and judge exactly what constitutes legitimate grounds for debate, and what

is hate speech shifting the terms of debate. Museum workers must avoid framing something which is not a question as a debate.

In this section of the toolkit Jen Kavanagh offers practitioners a set of considerations to address when working on potentially harmful acquisitions. These include reflecting on your organisation’s values, motivations, priorities, stakeholders and relationships when collecting hateful material. Sam Jenkins of

the People’s History Museum (PHM) presents a case

study relating to the display of harmful material from transgender exclusionary groups. Jenkins’ case study recounts the PHM’s response to the addition of anti-transgender rights material to an exhibit, and how the organisation attempted to acquire both trans-exclusionary and trans-inclusive material into its collection, without causing undue harm to staff, visitors, or community partnerships.

Further reading

Zolberg, L. V. (1995). Museums as contested sites of remembrance: The Enola Gay affair. The Sociological Review, 43(S1), 69–82

Collecting ‘hate’. Questions for consideration

Jen Kavanagh, freelance curator and consultant

Collecting contentious, sensitive and potentially harmful content is complex. But if museums are to be representative and balanced, there may be times when they should consider documenting material that relates to opposing sides of a debate. It could mean collecting information for context about the topic or issue that people oppose and are protesting about. Or it could involve acting as a sounding board for opposing views to be heard. Either way, collecting content that relates to hate, or is perceived as harmful or extreme, must be approached with caution.

Consider these questions when embarking on a collecting initiative for content of this nature:

• What are the values of your organisation? Would collecting this object or material go

against these and potentially harm your museum’s reputation?

• Whose views are of value and relevance? What is the scale and impact of the harmful views? Is it a

small isolated group or a larger movement that is likely to be remembered in the future? Would it be unfair or unbalanced to give them a platform over other groups and viewpoints?

• Where are your priorities when it comes to the people you engage with? Are you working with

a marginalised community where trust must be built and maintained? Would collecting something that criticised them (refugees or

migrants for example), damage the trust you are working hard to build?

• How can these hateful views be captured? For example, could an oral history with someone who

has been at the receiving end of abuse enable you to acknowledge the viewpoints of the abuser without having to speak to them directly? Are you sufficiently equipped to undertake an interview of this kind?

• Would hearing the views of the abuser directly add value and context to what you are looking to

document and record? Are your staff equipped to manage engaging with someone with extreme and harmful views? What training can you offer? What is your duty of care for those who work for and support your organisation?

• How can you balance acknowledging a viewpoint through acquiring content related to it, against

collecting material and potentially giving the impression you’re endorsing these views? How can your press and communications team support the way in which these decisions

are presented to the wider public and the communities you engage with?

• Are you collecting this material for documentary purposes, or collecting for the purpose of

display? If you don’t plan to display the object, is this sending a message that the museum is censoring what the public is able to view and access? If you wouldn’t display the object, is collecting it still valid?

Case study

Sam Jenkins, People’s History Museum

Project name

Contemporary collecting modern protest at People’s History Museum (PHM)

Project summary

As part of our exhibition Disrupt? Peterloo and Protest, People’s History Museum asked the public to submit examples of their protests through objects and comment cards.

A sticker was left on one of these cards in the exhibition and was later removed, due to connections with anti-trans activism and in line with museum policy for this exhibition.

After the museum removed the sticker, a protest was staged outside PHM by the movement ReSisters, with a counter-protest at the same time by Sisters Uncut*. Several objects were submitted from both groups to the Programme Manager, for display in Protest Lab and/or acquisition to the museum’s collection.

The museum therefore had to make several decisions: should we display the objects; should we collect them; and how could we do that without potentially alienating an important section of our audience?

*Editors’ note:

ReSisters are a group who perceive transgender acceptance as a threat to cis gender women’s rights and campaign against transgender people’s rights.

Sisters Uncut is a British feminist direct action group who are inclusive of transgender and non-binary people and protest for the rights of trans and non-binary people.

Project aims

Collect material from both sides of a contemporary campaign relating to a particular view on women’s rights, which opposes trans rights, without actively ‘taking a side’ in the debate.

Approach to collecting

We were able to use this event as a collecting opportunity thanks to previous conversations with colleagues about what we collect and our procedures for loans and acquisitions, meaning they were confident in what steps to take.

We accepted the objects into our care before decisions were made to ensure that the opportunity was not lost, and staff made sure that entry forms were signed for the objects to be identified, making no promises about the display or acceptance of the objects. The depositors were informed that the objects would be discussed by our acquisitions panel, as required by our collecting policies. This gave us time to consider the ethical issues around the acquisitions.

We first discussed if the objects should be added to the exhibition. The Programme Team, Collections Officer and Director met and agreed that the objects could not be displayed ethically with the limited interpretation available in the space, as the lack of context would increase the risk of alienating visitors. The depositors were then contacted with this decision, and informed that the objects would be discussed at the next Acquisitions Panel – keeping the owners up to date throughout the discussions.

When the Acquisitions Panel next met, we discussed the objects based upon our usual criteria – relevance to the collection, conservation/storage issues, and ethical issues. We agreed that the objects fit with the collecting policy

and were important to represent. However, we were aware that there could be ramifications for the museum by accepting the objects. With social media playing such a large part in both campaigns, it was possible that accepting the objects into the collection would be used as an endorsement of views, potentially alienating visitors or prompting requests to return the opposing view’s objects.

Before informing the donors of our interest, we drafted a statement that sought to counter any negative response that might damage the museum’s

reputation. We then contacted each donor, making sure that all context was fully documented, and staff were aware of the decision made.

Project outcomes

• PHM accepted objects into the permanent collection from two opposing views on a contemporary campaign.

• PHM was able to represent a very challenging subject area within the collection.

• PHM staff were better informed about what we do and do not accept into our collection.

What were the ethical considerations and challenges?

• Collecting items associated with this campaign could be interpreted as an endorsement of views that could alienate visitors and members

of community groups the museum had worked hard to include over the years.

• When trying to convince a donor to donate objects, it can appear that you might agree with a donor’s viewpoint but acting in this way could mislead

donors and could be unethical.

• Could it be unethical to refuse to display objects associated with a challenging topic but accept them into the collection – does this look like the museum is

trying to control what is said?

• When collecting material around an active protest that could lead to a backlash, is it ethical to collect knowing that staff may have to face criticism,

complaints or abuse?

• How do collections and museum staff remove their personal feelings about a subject from the collecting process?

Three lessons learned related to ethics

- Collecting objects associated with a divisive argument or contemporary protest comes with all sorts of ethical issues; are you being seen to endorse a particular view? By doing so are you alienating or othering any groups*? Can you collect without taking sides, and are you inadvertently misleading donors by suggesting otherwise? All these matters need to be considered by staff involved – and potentially the directorate – for an ethical decision to be made.

- You need to consider the ethics relating to staff as well. If you are collecting in an area you know might lead to a negative response (complaints, or a backlash) consider the effect it might have on staff in Front of House or Social Media teams who are more likely to face the brunt of it.

- There is no easy answer to ethics, and everyone will have a different opinion about what is and isn’t ethical. Work together to find the stance that fits with your institution, communicate it, and stick to it. Keep staff who aren’t involved in the decision informed about it and explain your reasoning, so they understand.

Editors’ note:

Othering is a process of stigmatising an individual or a group of people as different, undesirable or inferior to others in a society. It’s defined in the Oxford English Dictionary as ‘the perception or representation of a person or group of people as fundamentally alien from another, frequently more powerful, group’

Decolonisation of museums

Introduction

Ellie Miles, London Transport Museum

The subject of decolonisation is often presented in the media as a question that only concerns repatriation of artefacts. Work towards museum decolonisation includes addressing much more than this, and in doing so provides a useful critical lens to the work of acquiring new collections.

Understanding the harm that museums have done as part of colonial apparatus and systems, partly by reinforcing, exploiting and removing cultural property, is important. Repatriation is one way of addressing this damage; contemporary collecting may offer another.

Colonial collecting and historical representation has caused a great deal of trauma. Over time, museums have done harm by: presenting racist views, providing a platform for racists, excluding non- Western forms of knowledge, functioning as hostile environments for visitors and workers, representing trauma and suffering carelessly, and by taking money from sponsors who damage society.

Many of the most damaging colonial collections in museums were acquired contemporaneously. This is a legacy that today’s contemporary collectors must learn from. Such collecting practices have informed how museums process and manage acquisitions and information. In the past, collecting practices structured and ordered collections and knowledge to exclude people of colour from having power

and authority over cultural objects and values. It was part of a wider imperial system of exploitation, cruelty and harm. This is part of the historical context of collecting today, which a more critical approach to contemporary collecting can avoid replicating. Establishing new forms of equitable and non-extractive collection approaches and finding new methods to avoid re-enacting and re-inscribing damaging methods, are essential ways to decolonise contemporary collecting.

The toolkit offers vital insight from curators Rachael Minott and Charlotte Holmes on how to develop decolonialised collecting methods. The colonial role

of museums means that for many, the museum can never be entirely decolonised, yet decolonisation work in museums can make institutions more accountable, more equal and less hostile. Minott’s advice advocates for an awareness and redistribution of power between museums and people who have historically been excluded from those systems.

Holmes’ case study shows how contemporary collecting in Birmingham disrupted legacy working methods and built new, rich collections.

Further reading

Kassim, S., 2019. ‘The Museum is the Master’s House: An Open Letter to Tristram Hunt’ available at https://medium.com/@sumayakassim/the-museum- is-the-masters-house-an-open-letter-to-tristram- hunt-e72d75a891c8

Advice for decolonial practice in contemporary collecting

Rachael Minott, The National Archives (UK)

Decolonial practice is human-centric, democratic,

self-reflective, critical and active.

Working decolonially is a priority for all who strive for equality. Decolonising in museums is

understanding that the history of colonisation was as much about creating structures and framing knowledge, as it was owning and occupying land.

To establish and maintain political control over a quarter of the world’s population, colonisers adopted and promoted a mindset and culture of colonisation. This involved framing any difference of thought, appearance or actions as lesser, threatening or dangerous.

With contemporary collecting we can frame new narratives and offer contemporary histories and technological innovation in decolonial ways, but there is also the danger of replicating colonial structures.

Decolonising in museums is focused on decolonising minds, by inviting multiple perspectives, critical thinking and an acknowledgment (not erasure) of violent histories. Decolonisation is a continuation and development of a long history of best practice. The main change is acknowledging the violence that affected and caused the injustice, exclusion and inequalities we are addressing through inclusion work.

Decolonial practice actively seeks to redistribute power so that we do not continue to work in oppressive ways. Decolonising is a part of the fight for equal rights, but it must consider equity not just equality.

Equity requires acknowledging the historical imbalances in access, recognition and representation. It is not even-handed to provide for both the historically oppressed and the oppressors equally. Historically excluded groups need to be given more attention and resources than those who are currently overrepresented in workforces, narratives and user groups. It needs to

be acknowledged that this is a necessary part of the process of achieving real equality going forward.

Decolonising in museums begins with an acknowledgement of colonial histories and how they have affected:

• How we identify narratives worth preserving (and the absence and erasure of many

perspectives while projecting an image of neutrality)

• The understanding and valuing of expertise in museums

• By who, how and for whom are these new narratives interpreted

• Where, and with whom we share knowledge

In other words: knowledge creation, translation, display, documentation.

To do this when collecting new narratives and objects, one should ask:

• Whose knowledge is being used? Were permissions obtained to use this knowledge, and in this way?

• Who is being paid and is it proportional?

• Who is given credit (as individuals, as experts, on the permanent databases)?

• Who is given control (creative, financial,

managerial, and intellectual)?

• Who do the narratives collected refer to?

• Who is empowered to make choices over acquisition?

• Who will interpret these objects?

• Who is the envisioned audience for these narratives?

•

Are these narratives interpreted by the people whom they refer to, were those people involved

in the acquisition process, and are they the envisioned audience?

Therefore:

• Be human centric, by asking who/whom?

• Democratise: share decision-making, be that in relation to acquisitions, interpretation,

documentation or use of collection

• But be self-reflective: what are the power

dynamics at play? When we understand who is

being represented and who holds the power over the representation, we can more clearly see the imbalances of power at play.

• Be critical: Just because things were done in a certain way before, does not mean they are right

today. Always evaluate your practice and refine.

• Be active: noticing imbalances, talking about imbalances and striving to rectify these by

practicing equity, are different things. Be the most

active you can be in the fight for equality.

And remember that decolonisation is largely about self-determination and removal of oppressive systems and ways of thinking that are seen as intrinsic to colonisation. So, speak to those whom this affects the most, give up some of your power and some of your space so they can occupy more space and hold more power.

Case study

Charlotte Holmes, National Trust

Project name

Collecting Birmingham

Project summary

Collecting Birmingham was a unique project that, with funding from the National Lottery Heritage Fund (NLHF) and Arts Council England (ACE), significantly developed the relevance and accessibility of Birmingham Museums Trust’s (BMT) collections. During a three-year project, people from the Ladywood district

of Birmingham directly informed the acquisition of 1,801 objects. Collecting Birmingham brought new stories and objects into the permanent collection of the Museum; stories and objects that reflect and resonate with the lived experience of our city. These objects allow the Museum to tell the story of Birmingham in its true colour and vibrancy.

Project aims

• To strengthen the collection by acquiring objects and associated oral histories which engage local communities and allow us to tell their stories

of growing up, living and working in Birmingham (specifically the Ladywood district).

• To work with partner organisations in the district to develop a shared understanding of significant people, places and events in Ladywood

through the over-arching project theme of ‘growing up, living and working in Birmingham’.

• To build sustainable and continuing relationships with new audiences and local community groups through a new process of consultation-

led collecting.

• To increase the relevance and profile of Birmingham Museums to the people of the city, particularly the heritage sites, by using these locations

as centres for dialogue and consultation.

• To develop the skills, knowledge and behaviours of staff and volunteers involved in the project.

Approach to collecting

Birmingham is the youngest city in Europe. It is also ‘superdiverse’ with

a long history of migration. BMT has a significant track record of working with Birmingham’s diverse communities, but this diversity was not reflected in its permanent collection. Collecting Birmingham was a response to this lack of representation.

The Ladywood district of the city provided a geographical focus for the collecting. Eight key communities of faith and identity (including White English) were represented in the project.

In the first year of the project we invited local people to join focus groups, asking those people what Birmingham meant to them, and what they would like to see in the Museum. This process helped us identify themes around growing up, working and living in Birmingham. Participants in the focus groups tended

to be older and already engaged with heritage; they did not reflect the diversity of Ladywood. We also found that discussions tended to reflect ‘safe’ subjects such as leisure, rather than subjects such as race or faith.

In the second year we decided to change our approach, taking the conversation to Birmingham’s diverse communities. We went to Melas, schools, cricket matches, mosques, Pride, dances, and poetry evenings. We brought together contacts from the different events for in-depth round table discussions

about key acquisitions. We also invited community experts to join our existing advisory panel of heritage and arts experts. We were open and flexible; sometimes a conversation with a neighbour or colleague would lead to an unexpected opportunity to collect. This approach allowed us to talk and work with a wide range of people. Conversations moved from safe subjects to

real and sometimes difficult lived experiences. It also introduced us to some

amazing people who were instrumental in shaping new acquisitions.

Project outcomes

• BMT’s collections better represent its diverse communities

• Strengthened display, status and understanding of community history narratives

• More intersectional approach to community engagement

• Developed relationship with new stakeholders

• Informed the development of new collections development policies and procedures

• Deepened the trust and relationship with existing stakeholders

•

Challenged the ‘us and them’ of the Museum and its community

What were the ethical considerations and challenges?

Are museums safe places for all our histories and material culture?

Initial conversations with members of the public showed a degree of scepticism around the Museum’s intentions. Will objects be mis-represented, will our histories be forgotten or mothballed? We had to respond honestly to these challenges. BMT, like many museums, has a long history of important, but

short-term projects on marginalised histories. The short-term nature of these engagements, along with reduced funding, meant that many histories were forgotten, displays became tired and connections were lost.

What conditions are needed for members of the public to make meaningful decisions around collections acquisitions?

Most of our interactions with members of the public were one-off. Their opinions were recorded and were listened to. However, there were few opportunities to continue the discussion or to enter into more meaningful dialogue with the institution.

How can the market reflect value?

Collecting Birmingham was able to purchase objects from members of the public. A challenge was attributing a monetary value to objects with significant cultural value, but little market value. We found that members of the public associated museums with the collecting practices of empire; taking, rather than paying a ‘fair price’ for the material culture collected.

They also felt that the higher the price paid for an object the greater the Museum would value it, and therefore the better it would care for an object. Whatever we might say to this, when we think of our large underused stored collections, I wondered if they had a point.

Whose heritage is this?

When talking about communities in museums, we often refer to people not reflected in the Museum workforce. BMT has a relatively diverse workforce, in terms of class and race. Members of staff from a range of departments were able to put us in touch with key donors and vendors. When connecting with our communities and brokering relationships it was important to reflect on ‘our’ shared heritage in the city. Our diversity as a staff team really helped with this.

Three lessons learned related to ethics

- Go with the energy: messy and opportunistic collecting can work. Being open and transparent allowed us to make the most of unexpected opportunities to collect. Sometimes activities didn’t lead to collecting, but the relationships formed on the project informed other areas of practice.

- The way museums work is a barrier to inclusion. The pace, lack of transparency around decision-making and short-term nature of projects makes including ‘different’ people and our histories a challenge.

- Having a workforce that feels part of Birmingham and reflects its diversity

is invaluable.

Climate emergency

Introduction

Ellie Miles, London Transport Museum

In 2019 museums in the UK began to join the increasingly wide declaration of a climate emergency.

Some used interpretation to spread the message and some began using their programming to support young people on school climate strikes which have been taking place since 2018, usually on Fridays.

Collections work is also crucial in these efforts. The causes and material that have resulted in the climate emergency are included in collecting remits even though they may not be mentioned as such; we may come to understand our collecting policies as gathering evidence of climate change. For natural history collections this is established practice, and other museums document this too. Social history collections evidence the advent of mass plastic production. Disposable goods and single-use plastic products all point to the existence of climate emergency in our era, as do objects designed to counteract this.

Alongside the objects that evidence climate crisis, protest material relating to climate justice can

be collected too. In 2019 several museums in the UK acquired, preserved and displayed material from the Extinction Rebellion group of climate activists. This material has been collected as examples of design, local engagement and as maritime history, showing how broadly climate protest material resonates.

Some considerations for those engaged in contemporary collecting include thinking about how contemporary collecting activity can be carried out sustainably. Using low- or zero-waste resources during collecting work and plastic free, recycled and sustainable collections management equipment where possible, are all matters that people carrying out contemporary collecting can keep in mind.

As museum workers learn to address the climate crisis in our collecting, sustainable practice advice will improve. The case study in this toolkit, provided by Laura Boon of Royal Museums Greenwich, shows how one museum has used a relationship with Extinction Rebellion to present climate emergency to their audience and help develop their own working methods. The toolkit also includes a list of prompts for planning a low-waste collecting project, which will be updated in future.

Climate emergency questions and prompts

Ellie Miles, London Transport Museum

All collecting projects require resources, and those doing this work might consider these prompts throughout their work.

• What physical resources do we need to conduct our collecting project? How can these

resources be sourced to be sustainable? Can we re-use, reduce or find other alternatives? Are there commitments that we can hold ourselves accountable to? Can we commit to not using single use plastic and avoiding air travel?

• Which electronic devices are we using in this collecting project? What is the environmental

cost of using these digital resources? Can we loan devices from other projects or organisations if we need to use them? Are there alternatives?

• What materials are required to conserve this material? Can this be done sustainably? Do we

wish to commit to preserving this in perpetuity given its requirements?

• What travel and movement does this project prompt? How can this transport be made

sustainable?

• What by-products will our project produce? How can we ensure that any resources are re-used,

rehomed or broken down? Has this project produced material which may be of use to colleagues working elsewhere, or which might be better homed in other collections?

• How does what we collect represent people as actors in climate change? Are they represented

as consumers or citizens? Have we got a balance of representations of how people act and express agency?

• What material are we collecting that explicitly addresses climate change? What material are

we collecting that has implicit connections to climate change? How do we catalogue and document material so that this is recorded and communicated?

• Can we collect processes and intangible contributors to climate change? How do we

evidence and record nonhuman actors in climate change? How do we hold financial processes, economic practice and corporations to account?

How can we collect and preserve the effects of climate change? Are there ways we can document and record emergency events in our collections? Can we record the changes to climate in what we collect?

Further reading

Julie’s Bicycle, 2017. ‘Museums’ Environmental Framework’. Available at: https://juliesbicycle.com/ resource-museums-framework-2017/

United Nations [website] ‘About the Sustainable Development Goals’. 2019. Available at: https:// http://www.un.org/sustainabledevelopment/sustainable- development-goals/

Climate Museum UK, digital museum, [website]. Available at: https://climatemuseumuk.org/digital- museum/

Green Heritage Futures [podcast], Henry McGhie episode 3, April 2019. Available at: https:// juliesbicycle.com/news/podcast-henry-mcghie/ [accessed January 2020]

Drubay, D., 2019. ‘18 Provocations to the Museum Community to Face the Climate Crisis’ available at: https://medium.com/we-are-museums/18-

provocations-to-the-museum-community-to-face- the-climate-crisis-c2ac76475d54

Case study

Laura Boon, Royal Museums Greenwich

Project name

Extinction Rebellion: Polly Higgins blue boat at the National Maritime Museum (NMM)

Project summary

The National Maritime Museum, Greenwich displayed the blue Extinction Rebellion (XR) boat, Polly Higgins, nineteen days after collection from a protest site. The boat was displayed at the NMM from 8 August to 8 October 2019, with a traditional style object label and five protest placard style signs.

The Polly Higgins is one of the first six Extinction Rebellion boats. Extinction Rebellion first used a pink boat to block Oxford Circus for five days in April 2019. Even after the boat was impounded by police, the symbol of the boat continued to be used by the protestors. In July 2019 five boats, including the one displayed by the NMM, were used during protests across the UK.

Extinction Rebellion had planned to use the Polly Higgins boat on the afternoon of Friday 19 July 2019 at the school climate strike protest near the Houses of Parliament. In the early hours of Friday morning the police issued a Section 12 (Public Order Act, 1986) notice, which restricted Extinction Rebellion’s use of the boat, so this wasn’t possible. The NMM negotiated with the police to be able to collect the boat before it was seized.

Project aims

• The NMM explores our ever-evolving relationship with the sea. Increasingly this relationship is going to be shaped by the climate and ecological

emergency. The role of oceans in climate change mitigation and the impact that climate change has on oceans is often not understood or even discussed. The NMM wishes to become a space for this discussion.

• To use the boat as a platform to discuss the climate and ecological crisis, especially in relation to the ocean.

• Change the perception of the Museum – the bright boat and interpretation against the backdrop of the classical stylings of the Museum was

intentionally disruptive. It also challenged some of our visitors’ and local communities’ perception of what a maritime museum is.

• To act as a pilot for rapid response displays.

Approach to collecting

The boat itself was registered as a deposit rather than a loan as this enabled the boat to be displayed outside. Acquisition of the boat was not pursued as it is still an active object; XR wished to be able to use it in the future and from a curatorial perspective the blue boat is of less significance than the original pink boat. The National Maritime Museum also no longer collects small boats, with this part of the collection now closed due to storage restriction.

However, the more we engaged with XR the more we realised how central concern for the ocean is for many of their members. This is why we later chose to acquire the ten flags on the Polly Higgins boat, several of which have a maritime theme. We have since acquired an additional three Extinction Rebellion flags from their marine creatures’ series, and we are planning to collect any additional marine themed flags produced. As all Extinction Rebellion objects are communally owned, a representative has signed the flags over to the Museum. We will also be recording an oral history with one of the main flag designers. It is unfortunately not possible to record oral histories related to the use of the boats, as the pink boat has been used in an alleged criminal act. The Museum

is unable to accept anonymous oral histories, partly due to needing a named individual to assign copyright and being unable to ensure ongoing anonymity.

Project outcomes

• The NMM has created a cross-departmental working group to evaluate how

it can undertake rapid response projects in the future – including staffing,

logistics and if a dedicated space is needed.

• Generally, the response to the boat has been positive – even from people who are surprised to see it at the Museum. It challenged some people’s

perceptions, with some visitors assuming the Museum focuses only on the historical. From our local community there was positive feedback that the Museum was engaging with the topic of climate crisis, something many of our visitors feel passionately about.

• The more we engaged with Extinction Rebellion the more we realised how central concern for the ocean is for many of their members. This is why we

later chose to acquire the ten flags on the Polly Higgins boat.

• Unexpectedly the area around the boat at times became a public space. It is usually an unused piece of lawn, but we had a die-in and protest by Extinction

Rebellion at the start of the summer, and a love-in by Extinction Rebellion families in October. These events were independently organised by Extinction Rebellion but, as a positive response to the display, the Museum became a place of relevance in which Extinction Rebellion supporters could meet.

• Even more surprisingly non-Extinction Rebellion groups also held pre- arranged meet-ups at the boat, without informing the Museum. It was great

that it became a community space for those wishing to discuss the climate emergency (a university group on the solidarity strike day of the 20 September 2019) or air quality concerns (a group of local people campaigning against the Silvertown tunnel).

• Going forward we are continuing to engage with Extinction Rebellion. Extinction Rebellion have since hosted a Christmas toy and book swap at the

Museum and we are discussing future potential events.

What were the ethical considerations and challenges?

• The NMM had previously tried to collect the pink boat, Berta Cáceres, used

in the first Extinction Rebellion protest to feature a boat. However, the object

was being held as evidence by the Metropolitan Police in an undisclosed location. Ultimately our bid to display the pink Extinction Rebellion boat was unsuccessful due to police restrictions. Working with a group which commits acts of non-violent civil disobedience presents challenges.

• Ownership – Extinction Rebellion does not recognise individual ownership of

objects created for the organisation, such as the flags or even the boat. All

Extinction Rebellion objects are communally owned. Therefore, a representative

has signed the flags over to the Museum on behalf of the organisation.

• Engaging with a political organisation – as a national Museum there are restrictions on our activities. Extinction Rebellion is a campaigning

organisation. To ensure that we remained factual and unbiased, all the interpretation was reviewed by the NMM’s Executive Management Team.

• Not being a platform for Extinction Rebellion – in the initial meeting we were careful to have an honest dialogue with the Extinction Rebellion

representatives about the restrictions placed on a national museum with regard to engaging with Extinction Rebellion; we also established Extinction Rebellion’s requirements. Spending time with Extinction Rebellion was important to better understand their message, history and what objects we may wish to collect. This conversation was also vital for learning more about the reasoning for using the boat and beginning to build trust. We were very clear from the start that this was not a co-curation project and although Extinction Rebellion would remain the legal owner of the boat, the NMM would have sole responsibility for the interpretation.

• Police time and costs – the police were very professional and great to work with, which we appreciated, but the negotiations took time and a police escort

back to the Museum was a non-negotiable condition. However, the police were happy to support this, as it removed the need to seize the boat which ultimately would have been much more expensive for them.

• Sensitivity to Polly Higgins’ family and friends – the blue boat is named after Polly Higgins (1968–2019), an environmental campaigner and barrister. Higgins

spent the last decade of her life working towards making ecocide a crime at the International Criminal Court. There were sensitivities to consider, especially as this was a very recent bereavement. It was important that the

written interpretation and online articles reflected this and highlighted Polly

Higgins’ ongoing legacy.

• Editing rights – despite the boat remaining the property of XR the group had no editing rights over the content of the interpretation. However, we did keep

key contacts informed of our plans throughout the process.

• Re-using display materials – when displaying the boat, we ensured it was as sustainable as possible, in keeping with the ethos of Extinction Rebellion. All

the interpretation was repainted signage from the Museum that otherwise would have been skipped, the metal fence posts have already been reused within the Museum and the barrier rope was from a natural material rather than plastic and likewise has already been reused.

• Displaying close-up photographs of protestors – as it was not possible to trace individuals, we took the decision not to include any recognisable faces apart

from speakers on the main stages. Likewise, we did not include photographs of people being arrested or committing acts of non-violent civil disobedience.

Three lessons learned related to ethics

- Stakeholder management is vital but very time consuming. A grassroots organisation like Extinction Rebellion has a large and diverse number of stakeholders. The need for this continued throughout the display period.

- Trust takes time and has to be earned. Initially the NMM was considered by some members of Extinction Rebellion to be part of the ‘establishment’. Likewise, Extinction Rebellion was considered to be a high-risk group for the Museum to engage with. However, over time shared values have developed.

- Conversely it is also important when undertaking rapid response projects to consider the wellbeing of museum staff. Due to the lack of time and the short notice, staff from a wide range of departments had to assist on the project,

in additional to their already full workloads. For a unique project this is viable. However, longer term there is a question of how the Museum can ensure that enough capacity remains for short notice projects.

Trauma and distress

Introduction

Susanna Cordner, London Transport Museum

Contemporary collecting often involves being reactive – acting quickly and in response to events or developments, sometimes while they are still unfolding. This approach ensures curators can document in near-real time and collate collections that seek to reflect how things really happened. It also, however, raises issues around sensitivities and safeguarding, particularly when working on topics that might prompt or relate to a person’s experience of trauma or distress.

The reactive nature of this kind of collecting means that the usual preparations and due diligence procedures might not always be followed. Museums might not be equipped to give the support required, whether to those directly affected, to their visitors or even to their own staff (who have to both professionally and personally process this material and experience). In some cases, someone might

fall into more than one of these camps – perhaps by collecting material that relates to a personal experience they have had or by visiting a museum that has documented an event they witnessed.

In turn, the collection staff, who act as both the collectors of this material and the connection point between the affected persons and the museum, might be expected to fulfil a social or supportive role for the public for which they might feel ill-equipped. While, again, this kind of activity might take place at short notice, it is advisable for museums or a collection team to have procedures in place so that staff and public participants know what to expect and what kind of support might be available to them.

The permanency and uses of a collection that relates to trauma or distress can also result in ethical issues. Material or accounts that a member of the public might give whilst in the early stages of processing

an event for instance, might be something they feel uncomfortable having shared at a later date.

Similarly, a curator must be careful not to exploit or pressure a person in vulnerable circumstances when seeking material for a collection.

How this material is documented, disseminated and displayed is also very important. To do so without careful consideration of context could have a distressing impact on the source, staff and audience for this work.

Matt and Jess from the Museum of Homelessness offer incredibly important advice on working

with people who have experienced trauma. Jen Kavanagh’s case study from a project which aimed to collect the stories of disabled activists reflects on the challenges and considerations made.

Working with trauma

Matt and Jess Turtle, Museum of Homelessness

What is trauma? Trauma comes from exposure to difficult, painful or abusive experiences and can stay with a person for a long time. Research by Lankelly Chase in 2015 tells us that 85 per cent of people in touch with criminal justice, substance misuse and homelessness services have experienced trauma as children.

As museums develop more socially engaged work, it is important to think about – and have a good understanding of – trauma. It is also important to bear in mind that people may become homeless in part due to traumatic experiences and then are likely to undergo further traumatic experiences whilst homeless.

What does it mean? The effects of trauma can be emotional or psychological. There is also growing evidence that exposure to traumatic events as a child (adverse childhood experiences/ACEs) is linked to a range of health factors in adulthood such

as cancer, diabetes and chronic pain conditions. However, no one individual is the same and no life story is the same. In our work we should not make assumptions about people, but we should be respectful of how much strength and resourcefulness it takes to survive trauma.

Trauma and museums

Trauma is something, therefore, that requires very serious consideration and in our opinion is deeper and more complex than general understandings of ‘wellbeing’ at play in the sector. The best approaches to healing from trauma require cross- sector work, compassion and people driving the work who have similar experiences, but who have

had the opportunity to process them effectively. This piece, for example, has been co-written by a trauma survivor.

We believe that museums can play a role in healing processes and that collections work

can be a part of that. However, it is important to remember that museums can be exploitative institutions and that the act of collecting can,

even today, be experienced as extractive. When done well, it can be validating and empowering. A thoughtful approach is therefore required,

placing people at the heart of the process and being mindful of power.

Here are some top tips for working with people who may have experienced trauma, drawn from our own work over the last 5 years:

PRACTICAL BASICS

• Design stage Work with people who have experience of trauma, related to your project

theme, to design the project.

Recommendation: Recruit people to co-design the processes/project with you. Ensure you pay fairly for the role. You can achieve this by talking to people about what would work for them. For some people, volunteering is really important; some people need to be paid money for their expertise.

• Issues at the door? Start by asking yourselves what you’ll be asking of people. Cultural activities

often offer people an escape from the everyday experience, leaving issues at the door. However, collections or story-related work often means re- processing trauma. This can be really beneficial, but it’s important to be clear with people about what they are getting into.

Recommendation: Be really clear when you recruit to the project. Think about where there might be ‘triggering’ points in the project. Let people know what the process will involve so that they can make a conscious choice about involvement.

• Reflective practice Since running projects involves everything from tea-making through

to print deadlines, allowing space for people to reflect on what is happening in the project can easily be forgotten. It is important though, to leave space for issues that need more discussion to be unpacked.

Recommendation: Allow moments in the project for people to share and reflect. Try and make sure everyone gets a chance to speak if the project involves group work. If possible, work with a qualified reflective practitioner to run this session to ensure the space can be held safely.

• Quiet space If the project involves group work, or work with the public, having a quiet space for

people to take some time out is essential.

Recommendation: Quiet spaces don’t need to be grand but do consider accessibility. Does the

space have appropriate seating, lighting, and will it actually be quiet?

• Signposting Be aware of the limitations of the museum’s role. Whilst cultural activity can

be incredibly healing, we are not qualified for

everything.

Recommendations: Before you start your project make sure you have good connections with

other organisations that you can refer people to if they need help with health, housing or any

other things. As you develop the work, ask people about their experiences with partners so you

can make sure they are serving people well. The homelessness and social care sector is complex and not all organisations are right for every individual.

• Consider boundaries In doing this kind of work you’ll inevitably form bonds with different

people. This is one of the joys of the work. However, take care of yourself and ensure you have good boundaries. Receiving stories of people’s trauma can be very emotive and difficult work and healthy boundaries are essential for you and for participants.

Recommendation: Establish boundaries for yourself and the work. These could include keeping a balance between work and life, a ‘transitional ritual’ to help you leave work and enter the personal realm and a mechanism built in for you to process the work, preferably with a qualified practitioner. Whilst this may seem like a luxury, it really is an essential and has a long-

established precedent in homelessness and social care. Austerity has hit museums too and lots

of staff are already under immense pressure. If museums are serious about doing this work, then leaders must allocate budgets for it to be done properly. Show this to your Director, or Board if you are the Director, to help make the case!

POWER, TRAUMA AND COLLECTIONS

• To individualise is to pathologise People carrying trauma have often been labelled their whole life.

In society, ‘the problem’ is often located with the individual rather than structural inequalities and this can lead to increased stigmatisation.

Museums run the risk of enhancing this if we focus on individual stories rather than looking at the bigger picture. At the time of writing, we are living through ten years of austerity.

The impact of this on people’s lives cannot be underestimated.

Recommendation: It’s useful to actively reframe how we think about trauma and where it’s come from. Rather than thinking ‘what is wrong with you?’ think ‘what’s happened to you?’ When co-creating content, look at the wider picture together. For example, when we collect an individual object story for Museum of Homelessness, we always ask the person what they think should change, or what they would like to say to those in power. This highlights the structural as well as the personal and draws upon people’s expertise on wider political

and social issues.

• Who is ‘vulnerable’? Question your assumptions arounds labels such as ‘vulnerable groups’

or ‘marginalised communities’, often they are unhelpful. People experience trauma

in many different ways and to differing levels.

In addition, survivors of trauma are exactly that – survivors. This takes resourcefulness, resilience and creativity.

Recommendation: Avoid an approach which frames people as victims. Build trust with people. Be interested in the whole person, not the trauma story and only ask questions about people’s experiences when invited to do so. It is also good to be mindful that colleagues and volunteers may themselves be trauma survivors.

• ‘Being unwell’ rather than ‘wellbeing’ Sharing stories of trauma can be deeply affecting for

everyone involved. It is important to allow space for this in collecting projects and the process will not always be a smooth ride.

Recommendation: Be aware that the nature and depth of this work can create situations that

are unpredictable. This can run contrary to the institution’s desire to improve people’s wellbeing or deliver positive outcomes for funders/line managers and it should be borne in mind. It doesn’t mean the work is not powerful or meaningful,

but improving wellbeing is not always simple or immediate when dealing with trauma.

• Pay attention to power Be mindful of how people in the project will relate to you and each

other. An intersectional group can bring different power dynamics and it is really important to think carefully about this so that everyone feels heard and respected.

Recommendation: For group activity, ensure the facilitator has the skills to manage nuanced power dynamics. For work with individuals, always be mindful of your own privilege and assumptions. Give space and listen.

•

Consent People enter collecting projects for all sorts of reasons but their feelings about the project

or relationship with institutions may change over time. People’s entire life situation may change, and they may not want that previous experience held in the collection. It is important to allow for this in working with people.

Recommendation: Allow entry and exit routes for people in the project. If possible, give people the power to withdraw themselves and their contributions from the process – including objects, photography and other material. This offer will make people more secure about being part of your work, since you are prioritising them over the project outputs. Museum of Homelessness has ‘the power of veto’ written into our acquisition processes on a legal basis, meaning that people have the right to withdraw their objects/stories from the collection in perpetuity. No questions asked.

• Narrative control How will people be represented? How much can you ensure a story is

in a person’s own words?

Recommendations: As far as possible, democratise the interpretation process. After consideration,

we conclude it is not possible to ever be fully authentic and ethical when telling people’s stories. Museum processes have an inherent extractive power dynamic built in. However, processes like power of veto, enabling people to do their own documentation or write their own labels and genuinely putting people at the heart of your own work will help work towards it.

Further reading

Research on severe and multiple disadvantage from Lankelly Chase: https://lankellychase.org.uk/resources/publications/ hard-edges/

The original CD-Kaiser ACES study: https://www. cdc.gov/violenceprevention/childabuseandneglect/ acestudy/about.html

Piloting and analysis of ACES informed work from Health Scotland: http://www.healthscotland.scot/media/2676/ adverse-childhood-experiences-in-context- aug2019-english.pdf

Case study

Jen Kavanagh, freelance curator and consultant

Project name

Fighting for Our Rights

Project summary

In 2017, Kingston Centre for Independent Living (KCIL) partnered with Kingston University to capture oral histories and objects that tell the story of disability rights history in the Royal Borough of Kingston upon Thames. Kingston was at the forefront of the disability rights movement from the 1960s and was the first

place in the UK to trial an independent living scheme. This history had never been formally captured, and so KCIL’s 50th anniversary became a suitable moment to collaborate with those who have played a role in changing the lives of disabled people through positive action.

Project aims

• To capture the stories of people and organisations who have played a role in the establishment of Kingston’s independent living scheme

• To listen to disabled people across the borough and document their experiences of living with a disability in Kingston, in a way that they felt was

representative

• To train student nurses from Kingston University as interviewers, enabling them to conduct oral histories and learn from the interviewees’ experiences

as part of their clinical training

• To present this history to the public through a new website, touring exhibition, school resource and permanent archive at Kingston

History Centre

Approach to collecting

‘Fighting for our rights’ was a project initiated by KCIL, an organisation that provides a range of services to make sure that disabled people who live, work or study in Kingston are able to lead independent lives. The aims of the project stemmed from KCIL and its service users, many of whom had been major players in the disability rights movement in the UK. It was widely acknowledged that this important history had never been documented, so through a partnership with Kingston University and funding from the NLHF, the project aimed to address this.